A Grand Ole Opryland Betrayal: “The Dumbest Thing Nashville’s Ever Seen”

“And the people that were responsible for it, I would think today would look back on it and say, ‘Yeah, it was a dumb, dumb decision.’”

“The dumbest thing I’ve ever seen.”

–Bud Wendell, former CEO of Gaylord Entertainment

There are bad business decisions. There are tone-deaf ones. And then there’s the kind of decision that makes an entire city wince in unison. Better yet, explode in outrage. A mass, blood boiling that doesn’t (and hasn’t) fade with time.

You wanna kick a hornet’s nest? Walk into any given Nashville community and drop the name Opryland USA.

Why?

One minute, Nashville’s identity is a bespoke theme park put on by the minds who tuned the Grand Ole Opry to perfection. The next minute, that critical lifeline is being severed in its prime, quite simply, just because.

Shrugs.

Why not? What if? We’ll see.

You’d think CEOs are paid the big bucks not to follow whims like falling leaves. That million-dollar titles come with thousand-page reports. Strategy decks. Market projections. Financial forecasts run through the machine again and again until the math sings sure.

Right?

…

Right?

“Great shows! Great rides! Great times!”

It’s 1997. Opryland USA is bucketing millions in attendance each year with its antique locomotives, country ballads, psychedelic roller coasters, and Roy Acuff sightings on sunny park benches. This is a song Opryland has been singing since the very beginning, without a flat note or missed beat, and with no sign of tiring yet.

It’s a successful, one-of-a-kind theme park in its prime. Profitable. Loved. Everyone is winning.

The CEO sits back in the success — having spent decades making a career of the Grand Ole Opry and Gaylord Entertainment, overseeing Opryland from its infancy through its golden years. And at last, he’s settled with retiring. Business is in the perfect condition for a new set of hands to take over the reins. The future is promising.

Bud Wendell passes the baton to CFO Terry London. Inheriting the Gaylord country music brand and a theme park that’s only ever known net profits, London was handed a golden opportunity. The perfect setup to start his tenure off on a high note.

So, as any other would certainly do in his position, he decided that malls must make more money than theme parks and so had Opryland closed before the year’s end. Rides and attractions were actively dismantled while the park was still open in its final days.

Having no sentimentality for Opryland or Gaylord’s other properties, London undoubtedly underestimated Nashville’s reaction.

An eruption.

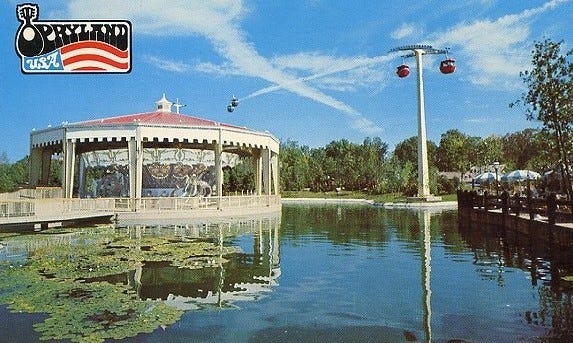

The city — office holders and soccer moms alike — furious and blindsided. Despite their heartbreak and betrayal, they understood the common sense truth: no one drives across state lines for J.C.Penney’s. But, they did for a theme park where music swooned and joy took the shape of a lakeside carousel hand-carved in Germany.

It devolved into a mess. “The dumbest thing ever seen.” An ordeal that Gaylord themselves regret to this very day.

Who wouldn’t?

They had a mine miles deep into the Earth, filled endlessly to the brim with diamonds and gold, but unceremoniously plugged it in with concrete for them to stand on while they took up a new whim of turning trees into mulch. Because that would be more profitable instead. Don’t ask for any verifiable data to back that up.

Today, every time a Gaylord exec hears the word Dollywood, a heavily loaded sigh follows.

Wendell said it himself, not burying his thoughts in boardroom euphemisms…

Opryland was not failing, flailing, or even trailing. It made money. It made memories. It made Nashville. And it made no sense to rip it up and replace it with a dying retail concept.

Opryland USA closed forever.

Barely two years later, Terry London resigned.

“America’s Musical Showpark”

If you find a Nashville native of a certain age — someone who remembers when Lower Broadway still had ghosts in the windows — and you ask them about Opryland, you had better have a seat.

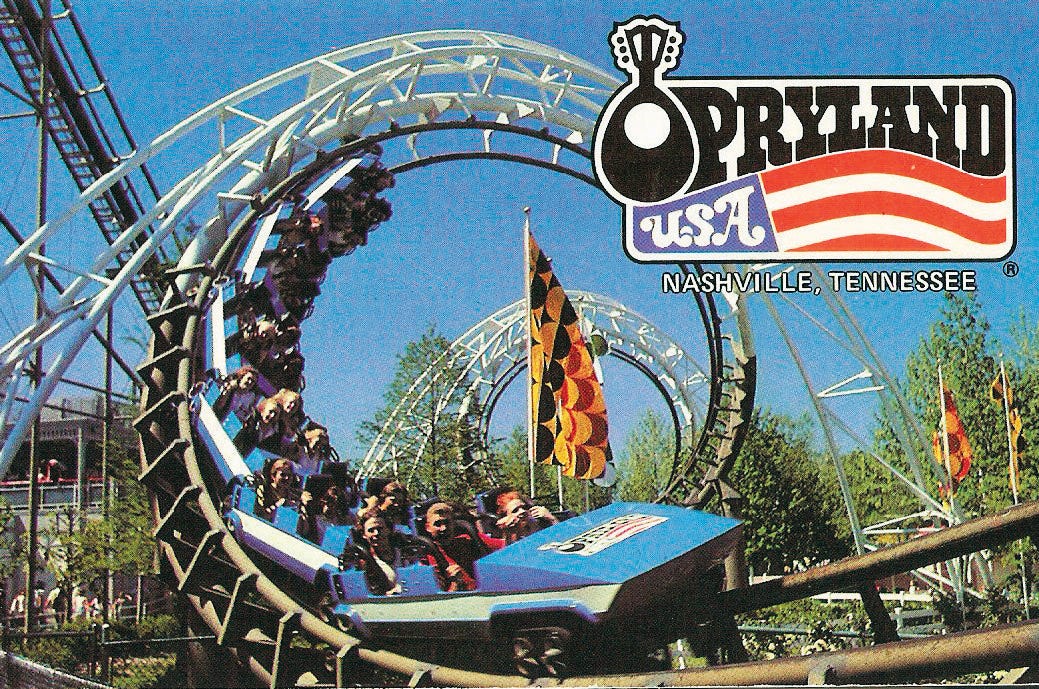

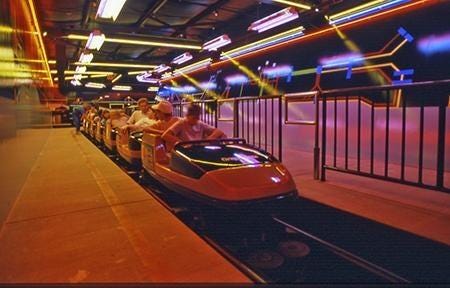

You’ll hear about the Grizzly River Rampage, a water ride so wild it essentially qualified as an Olympic training course. You’ll hear about Chaos, the psychedelic indoor roller coaster with its light show set to symphonic madness, the only one of its kind in America. Or Screamin' Delta Demon, a bobsled coaster that didn’t run on tracks so much as momentum and pure nerve.

But the park wasn’t just the rides. Opryland USA was music incarnate — a theme park where the soundtrack didn’t blare from overhead speakers, it came from the people around you.

String bands on porches. Four-part harmonies drifting through the air like kettle corn steam. You could be halfway through a funnel cake and find yourself front row at a gospel set with harmonies sharp enough to cut glass.

The shows weren’t background noise; they were the spine of the experience.

You didn’t go to Opryland to escape the real world. You went to see the best parts of it amplified and sung back to you in perfect pitch.

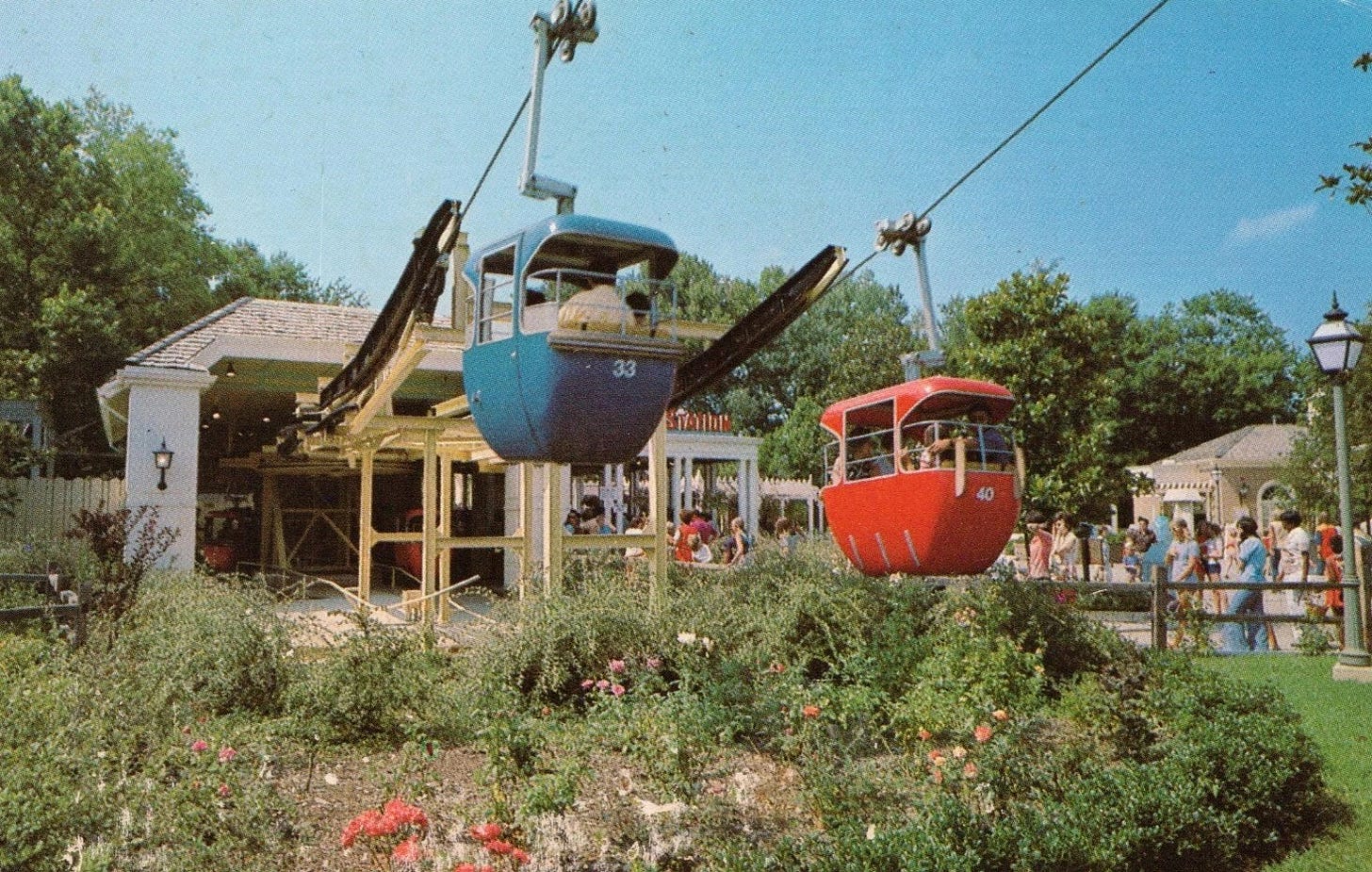

A symphony that was complimented by a railroad with restored antique engines named Beatrice and Rachel, both of which looped through the trees and whistled their own tunes while showing off the park’s softer side. Everything at Opryland had a rhythm.

And if you were local? The park was your backyard. Season passes. Post-church afternoons. Teenagers in name tags learning how to run shows, work tech, or operate roller coasters. It was a rite of passage as much as it was a theme park.

Opryland wasn’t trying to be Disney. It wasn’t trying to be Six Flags. It wasn’t trying to be anything other than what it already was — a musical celebration planted firmly in Tennessee soil with a banjo in one hand and a corndog in the other.

The park was, without exaggeration, the single most important reason tourists visited Nashville in the 70s, 80s, and 90s. Opryland USA put the city on the map. It built the industry around it.

The Opryland Hotel thrived because of it. The Convention & Visitors Bureau credits it with establishing Nashville as a destination, long before the honky-tonks started charging covers.

And for twenty-six years, it worked. It worked beautifully.

But of course…

It started as a rumor.

Late summer. Staff whispered it first. A chill in the air that wasn’t the onset of autumn. A murmur that Gaylord, flush with profit and praise, was yet considering cutting the cord.

However, this was met with an amazing response.

“That’s a ridiculous idea,” said Vice President Alan Hall to the Nashville Banner on August 30th, “We’re not going to level the park.”

Ridiculous.

November 4th would disagree entirely. Opryland was closing by the end of the next month. New Year’s Eve.

Fallout was immediate and immense. The company’s reputation and relationship with Nashville sank. And all the more delusional yet, Gaylord thought that the public opinion would turn around with the mall.

“They’re upset. Their parents are upset,” admitted the very same VP aforementioned, “We understand that.”

“We’re building a new entertainment tradition,” the CEO tried to appease to no avail.

Because that’s exactly how people characterize a mall.

There was no transition plan. No long-range vision. There wasn’t even, according to Gaylord’s own later admission, a strategic analysis. They just did it.

CEO Terry London partnered with The Mills Corporation, a retail developer with big promises and bigger renderings — IMAX theaters, an ice-skating rink, maybe a ride or two in the parking lot (to soften the blow).

Early plans mimicked the Mall of America, a commercial fantasyland with just enough razzle-dazzle to distract you from the flashbacks of the better Opryland that used to be.

Spoiler alert… none of that ever materialized. Reiterated, there was no plan.

The community howled. Petitions were launched. Editorials published. The mayor’s office issued a letter that curbed the slightest of hopes: “To preserve the park in its current form seems to be virtually impossible.”

And in three weeks’ time, the rides were sold off to Premier Parks — Six Flags’ parent company — for about $10 million. Hangman was rebranded as Kong in California. The Screamin’ Delta Demon and Chaos were dumped in a field in Indiana, where they sat rusting like abandoned carnival junk before being chopped up and sold for scrap.

The cost of the closure was a financial loss for Gaylord, especially after they sold their 33% stake in the new mall.

A mall that opened in 2000 — too late and already out of date — finding itself trying to tread water, sometimes quite literally.

Opry Mills was built in a flood zone, sitting primarily on what was Opryland’s parking lot. In turn, the bulk of Opryland itself became the mall’s parking lot.

The Mills Corporation proceeded to struggle with bankruptcy for years. Online shopping was already proving to have an impact. Nashville’s tourism predictably collapsed, down 40% in the summer and 20% overall. 9/11 furthered the tourism downswing. And all around, it took Nashville 6 years to recover to pre-park closure numbers.

Unsurprisingly, Opry Mills underperformed. The Mills Corporation got bought out. A flood drowned the mall in ten feet of water and rendered it out of commission for two years. Flood insurance was stripped to ¼ coverage because the retail site was (drumroll) knowingly built in a flood zone. And as for Gaylord Entertainment? They were spiraling, lost, with no way forward.

Oh, and the abandoned ruins of Grizzly River Rampage proved to be the only “ride in the parking lot” of Opry Mills to materialize from those cheap promises.

By the end of 2000, Terry London stepped down.

“Home of American Music”

New CEO Colin Reed joined the company in the beginning of 2001, and his first line of business was asking, “Why did we close that theme park?” After all, he reasoned that guests needed a reason to stay for three days, not three hours.

Finally, logic at last. Unfortunately, arriving a little too late.

Reed went on to call the decision of closing Opryland “a bad idea” after stating that the majority of his first year as CEO was spent dealing with the fallout.

In 2012, Gaylord tried to resurrect the magic with a new theme park venture alongside Dolly Parton and Herschend Family Entertainment — a would-be revival near the old Opryland site. But the deal unraveled when Gaylord revealed it was selling out to Marriott International, and the proposed park would be part of the corporate handoff.

Dolly, never one to let a hotel chain dictate a dream, backed out. The comeback canceled.

“Gaylord makes decisions that they feel are good for their company and their stockholders and I have to make decisions based on what is best for me and the Dollywood Company. Governor Haslam, Mayor Dean, and all the folks in government have been great to work with. I really appreciate their support through this process.”

And with that, the ghost of Opryland remained exactly where it was, a paved over parking lot for Opry Mills.

Yet... Opryland lives.

Not in ticket sales. But in Nashville’s memory. In the sound of a train whistle that no longer blows. In photos dug out of junk drawers. In a carousel horse someone swears they saw in a warehouse once.

And if you ask the people who lived it, they’ll tell you it was worth more than any mall.

“And the people that were responsible for it, I would think today would look back on it and say, ‘Yeah, it was a dumb, dumb decision.’”

–Bud Wendell, former CEO of Gaylord Entertainment