Queued for a Coaster, Survived by Accident: The Terrifying Triplets

Back when safety was a suggestion and rides required waivers, not tickets.

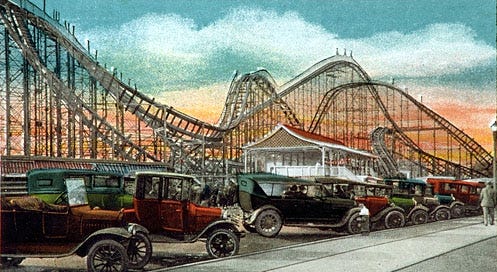

In the 1920s, the only thing wilder than Prohibition was the roller coasters. Full stop.

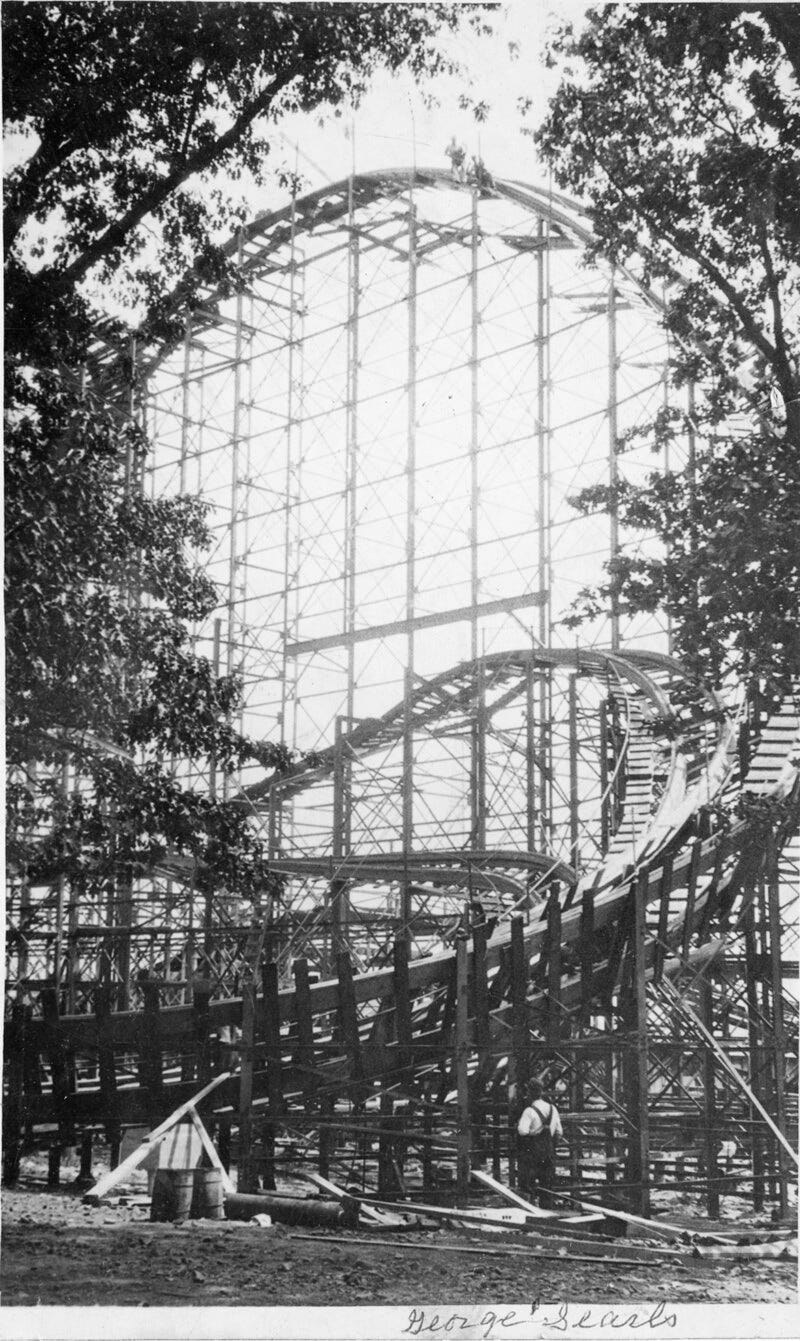

And no coaster has ever embodied chaos quite like the Terrifying Triplets: the Crystal Beach Cyclone, Revere Beach Lightning, and Palisades Park Cyclone. Born from the fever dream of designer Harry G. Traver, who most definitely said, “what if we required waivers to ride instead of tickets?”

These rides weren’t built for fun. They were built to test your will to live.

At least, that’s what their riders would say.

They called them “rib ticklers.” Tracks twisted like a nervous breakdown. Ambulances on standby, not as an exaggeration, but as protocol. It was the golden age of wooden thrill rides, when safety was a suggestion and adrenaline was the only ambition.

The Terrifying Triplets. America's first dance with death-by-design.

The Crystal Beach Cyclone (Ontario’s crown jewel of carnage) came with a nurse stationed at the exit and a warning sign that basically said “ride at your own peril.” The Lightning in Revere Beach, MA was so brutal, it lasted less than a decade before locals demanded it be euthanized. And the Palisades Cyclone? Let’s just say it lived up to its legacy from where it sat on a cliff’s edge until flames put it to rest in short order.

These were prime examples of just because it could be done, doesn’t mean that it should be done.

But here’s the thing. People loved them. Lined up for hours to be battered senseless. All despite a regional phase being “take her on the Lightning” for folk remedy reasons that replaced Plan B. The broken ribs. Collarbones.

So seriously. On the opening day of one, a child fell to her death. The coaster was closed long enough to remove her body and then the next train was dispatched. All of 20 minutes.

Opening day of another? A man was thrown from the train to his death and hit by the very same train seconds later. The culprit? A failed lap bar.

“Cyclone watching” swiftly became a thing. Parks offered prizes to anyone who could manage to ride three times in a row. Popular lore insisting that splints were sold outside of the Crystal Beach Cyclone.

These were the days that the concept of regulations was laughable. The same era when you could take your infant on a roller coaster and the infant would be the only one uninjured when it crashed. A coaster called the Rough Riders, in case you were wondering, and was closed for killing seven people within five years. It just kept derailing.

And you’ll never guess who designed Rough Riders.

A real example of the duality of man is one who conceived something as maniacal as the Terrifying Triplets and yet something as wholesome as the Tumble Bug.

There’s something to say about rosy retrospect when it comes to amusement parks. They were truly charming and quaint, albeit… imperfect. But, you will walk away with a more heartfelt appreciation for modern day regulations the more you learn about them.

Being able to enjoy airtime and butterflies without a cracked collarbone or broken rib. People watching without the worries of a rider taking flight.

Back then, coasters were closer to violence than science. They were rattling, unforgiving machines of masochism — and they were adored all the same. Rides were designed to make you question if you were really living if you weren’t challenging death. For fun. Recreationally.

And you wanna know the real kicker? Officially, the Terrifying Triplets were marketed as the Giant Cyclone Safety Coasters. No kidding.

“My most memorable ride in an amusement park occurred in July 1945, when I was on military leave in St. Catharines, Ontario. I had just turned 18 and had been in the Canadian Army for about 8 months. My two buddies and I spent a part of our leave in Crystal Beach, Ontario, which at that time was considered to be one of the greatest places for servicemen to have a good time.

Besides, Crystal Beach was famous for having the most thrilling roller coaster ride in the Western Hemisphere. Being soldiers of course, and having been trained for all kinds of warfare, we had ‘no fear’ of anything, except perhaps Military Police, and since we were on a legal pass, there was ‘nothing to fear.’

As soon as we entered the park one evening, we headed straight for the roller coaster, which was identified with a huge sign announcing ‘The Cyclone--Thrill of a Lifetime.’ After listening to the loud screams coming from the roller coaster, we decided that we must go on it right away, and promptly bought our tickets, which were I think about 15 cents or maybe 20 cents.

We then stood in the line-up near the entrance gate, which happened to be very close to where the previous passengers got off. It was then that I first noticed the distinctive smell of vomit which was stronger as we got closer to the loading point. It was a bit disconcerting, but I was then immediately distracted by getting a whack in the face from something kind of leathery. It turned out to be a wallet which had fallen from the ride, and we opened it and it had a US Navy ID Card in it. As soon as the ride stopped, we saw the US sailor getting off the ride and called to him. He looked a bit dazed, and did not realize what had happened to his wallet.

It was then our turn to ride, and we ran to the coaster cars. Up the steep ramp we went, up, up and then up some more until we could see the entire amusement park. Just as I was enjoying the view, the car lurched forward and I looked in front of me down a steep incline that looked to me to be about an 89 degree slope. The cars then headed down the incline at warp speed, and all I could see in front of us was Lake Erie.

I was sure there must have been a part of the tracks missing, and I then uttered my only two words during the entire ride... ‘Jesus Christ!’ ...as we plunged down towards the Lake, I then saw a steep bank to the right of the incline and we changed directions in a split second, turning violently on our side as the car careened around a hairpin turn. I looked sideways and saw the earth spinning by, and from that point on, most of the ride was pretty much of a blur.

The only other memorable part was as we reached a high horizontal point again, we were racing around a curve at such speed that it seemed certain that we would fly off into thin air. Very frankly, I was quite relieved to see the cars finally slowing down...even then, they approached the unloading platform at such a speed that one would think they would overshoot and go right into the spectators.

When I walked off the unloading platform, I couldn't help but smell the vomit again, and in fact, walked away from the area fairly promptly in order to resettle my own stomach.”

–Ed Mills, a survivor of the Crystal Beach Cyclone